He was initially intrigued with India as a potential market for his method; here, rice was the food staple. The methods used to mill it were, at best, primitive beyond imagining.

Natives brought the rice from the fields in baskets and dumped it into tanks of boiling water. They used a "bite" test to determine tenderness. Then they drained the water and steamed the rice by running coils through the mass. The rice was spread on a concrete drying platform and, unpleasantly reminiscent of some wine processing, workers would shuffle through the grains to dry them. This was a repellent task. The rice often developed a pronounced odour: men employed to mill it would be more than slightly noticeable for a period of several weeks, especially in crowded rooms.

Erich Huzenlaub was rightly appalled at this method, at the broken grains which resulted, and at the generally inferior and unappealing quality of the finished product.

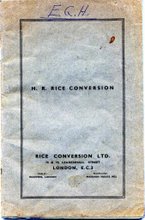

Using a special steeping and steaming process in their London laboratory, Huzenlaub and his associates developed a new process which was to improve rice nutritionally, and in many other ways.

Huzenlaub was on the brink of discovering parboiled rice. When Forrest Mars, Sr. (then in Britain) got wind of the development, he was immediately interested.

"Take that rice process with you to America," Forrest was advised. "Get away from the bombs and start a factory to make a product which could be of inestimable help to our forces during the war."

At first Forrest was deaf to this plea. The outset of major hostilities did not appear to him to be a propitious occasion on which to launch a new enterprise. Still . . . still, he was always very much alive to what could be an exciting possibility. Mars finally located Huzenlaub in London, and after talking to him persuasively, became a joint owner of the patent for the invention on 7 July 1941.

At about this time, far away in Houston, an enterprising food broker called Gordon Harwell was experimenting with rice preparation in his garage. This was a somewhat primitive endeavour but Harwell nurtured a fervent hope: that he could arrive at a better milling method.

* * * * *

From the Washington Post of 14 January 1944: "Converted rice may well create a new vitality in rice-consuming peoples of the Far East and the Americas which will add abundantly to the wealth and well-being of the world."

* * * * *

* * * * *

Harwell was not a chemist or a scientist, but he was firmly convinced he could preserve the natural goodness of rice somehow; a special cooking process was what he was trying to achieve. He fitted a home pressure cooker with a number of gadgets and began a series of experiments, most of which were fruitless.

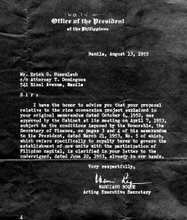

The ultimate breakthrough came to Harwell through a deceptively simple and obvious source: the mail.

A friend, sympathizing with Harwell's futile struggles, had heard about a booklet published by one Erich Huzenlaub. This book outlined Huzenlaub's patented method for preparing rice which appeared most promising. It was the answer to a prayer.

Harwell bombarded Huzenlaub with letters and cables, finally resorting to the then expensive expedient of phoning the UK scientist, a procedure which taxed Harwell's finances and patience to the limit.

As it transpired, Huzenlaub was largely indifferent to Harwell's entreaties. Huzenlaub wanted to set up mills in India and other big rice-consuming countries. The war had unceremoniously intervened. What did America's paltry four pounds per capita of rice yearly matter when stacked up against India's average of 350 pounds per capita?

Nonetheless, Huzenlaub was mildly intrigued. There was a rumour that he had profited exceedingly from some patents he had held for cornflakes, and that early manufacture of this breakfast repast emanated from his invention. Huzenlaub had the true European's vision of the US: the streets were really paved with gold or dollar bills. It was an alluring prospect.

Eventually Huzenlaub made the trip to the US but primarily because the war (WWII) had dried up his other options. He was a man who relished seeing his inventions put to practical use.

Huzenlaub also made the journey at the urging of Forrest Mars, who was, as usual, vociferous in his demand for some sort of action. Besides, Forrest, as joint owner of the patent, thought it was high time some return on his purchase of half interest should be realized.

The "Huzenlaub Process" (converted rice) has been hailed by its more ardent adherents as the first real innovation in rice-milling methods for 5000 years.

To comprehend the extent of the revolution in rice that was now to occur, it is first necessary to study conventional milling methods.

Rough or "paddy" rice, which is unhulled rice, has a fairly loose outer husk and three tighter inner skins. These four layers contain the various factors of the vitamin-B complex as well as the minerals.

Millers who produce plain ordinary white rice are devout believers there is a popular demand for food that is white. Their process removes all four coats, leaving a pearly grain consisting mostly of starch.

As a final step the grain is often coated with talc and glucose to provide an appealing lustre.

Some cooks still toss their rice into a container to allow water to run over it in the belief they are removing the talc. When ordinary rice is rinsed, any vestige of vitamin-B has been efficiently lost.

By the Huzenlaub Process the unmilled rice is cleaned and placed in a vacuum tank where the air is sucked out of the grain. Hot water at extremely high pressure is forced into the emptiness thus created.

The B vitamins, being soluble in water, are thrust into the centre of the grain with great pressure. Steam is applied to seal them there.

When the rice is dry, milling machines remove the husk and skins leaving tough, cream-coloured kernels whose nutrients cannot be rinsed away.

The surface starch is removed in the process, vastly improving the cooking quality of the rice and preventing the served product from being soggy, unpalatable mush. This finished condition had repelled many discerning homemakers.

Most importantly, as subsequent events were to confirm, the hard, gelatinised kernel is almost totally impervious to infestation.

Pesky weevils can bore their holes in rice that has been traditionally milled with impunity but can't lay their eggs in the smooth, hard kernels that result from application of the Huzenlaub Process.

* * *

Erich Huzenlaub visited a number of rice millers in Louisiana, Arkansas, and Mississippi. These were large and successful operators who were not particularly keen on the relatively high additional expense of rice milling inherent in the Huzenlaub Process. After all, it had never been tried; people seemed quite content buy ing "ordinary" rice in satisfactory quantities, thank you.

What was Huzenlaub talking about? Who was this European, anyway?

This long trail of discouragement had understandably brought Huzenlaub to the brink of defeat. When he reached Houston in 1942 there was one ray of light. Gordon Harwell made enthusiastic proposals, but even after the string of rejections, Huzenlaub was still unmoved. Harwell was not a rice miller; he was a food broker. Harwell's scientific knowledge was laughable.

Harwell may not have resided in the halls of academe but he was a force that could be reckoned with: a man with a vision and determination. He was indefatigable and hurled every argument at Huzenlaub. The more Harwell implored, the more massive the indifference of the inventive Huzenlaub. Harwell was almost prepared to admit total defeat...

He reluctantly drove Huzenlaub to the airport for his return to England and watched his only hope for success walk to the waiting plane.

Then fate stepped in...

When Huzenlaub was boarding the plane, somehow he stumbled, fell heavily, and broke his shoulder.

Huzenlaub was then confined for two weeks in a local hospital — a captive audience for the insistent broker. Harwell became a frequent and solicitous visitor to the suffering patient who had no other acquaintance in Houston. Harwell brought the traditional grapes, candy, flowers, and an unceasing flow of reasons why he should be allowed to adopt the coveted Huzenlaub Process.

When his convalescence was finally over, Huzenlaub had consented to an arrangement whereby Harwell was licensed to develop the new style of parboiled rice in the United States.

There was one condition: Harwell had to have a plant in operation within a year.

There was now a crying need for an infusion of hard cash. Harwell had a big stock of dried fruit on which he had already borrowed considerably. If he mortgaged his house and sold the fruit the proceeds could still never—even remotely—finance the purchase of the necessary building and equipment.

Harwell had a silent partner who now became plaintively vocal: "I'm 70 years old and not really vitally interested in investing in any project that isn't going to pay off for another ten years," he stated.

Forrest Mars had kept his ear tuned to these events: he had found Huzenlaub and had financed his trip to the United States, owned part of the Huzenlaub Process patent, and was well aware of the deal. Nevertheless he appreciated Harwell's persistence and enthusiasm.

"I have the ability to raise money," Mars informed the Houston food broker. "Sell me a half interest and I'll go into business with you." It was an offer the silent partner of Harwell found irresistibly attractive and he gladly left the new consortium to their own devices.

Forrest's Houston bank accountant questioned the wisdom of his loan application.

"What do you think I should pay for a half interest in this Harwell project?" Forrest asked. "I'm leaving for Chicago in 30 minutes. Send me the results of your thinking there."

The accountant did some digging, came up with a figure of $100,000, and was promptly told to make the offer. It was quickly accepted. Forrest was pleased with this transaction and offered the bank accountant a job which, some years later, developed into the presidency of the company.

Erich Huzenlaub visited a number of rice millers in Louisiana, Arkansas, and Mississippi. These were large and successful operators who were not particularly keen on the relatively high additional expense of rice milling inherent in the Huzenlaub Process. After all, it had never been tried; people seemed quite content buy ing "ordinary" rice in satisfactory quantities, thank you.

What was Huzenlaub talking about? Who was this European, anyway?

This long trail of discouragement had understandably brought Huzenlaub to the brink of defeat. When he reached Houston in 1942 there was one ray of light. Gordon Harwell made enthusiastic proposals, but even after the string of rejections, Huzenlaub was still unmoved. Harwell was not a rice miller; he was a food broker. Harwell's scientific knowledge was laughable.

Harwell may not have resided in the halls of academe but he was a force that could be reckoned with: a man with a vision and determination. He was indefatigable and hurled every argument at Huzenlaub. The more Harwell implored, the more massive the indifference of the inventive Huzenlaub. Harwell was almost prepared to admit total defeat...

He reluctantly drove Huzenlaub to the airport for his return to England and watched his only hope for success walk to the waiting plane.

Then fate stepped in...

When Huzenlaub was boarding the plane, somehow he stumbled, fell heavily, and broke his shoulder.

Huzenlaub was then confined for two weeks in a local hospital — a captive audience for the insistent broker. Harwell became a frequent and solicitous visitor to the suffering patient who had no other acquaintance in Houston. Harwell brought the traditional grapes, candy, flowers, and an unceasing flow of reasons why he should be allowed to adopt the coveted Huzenlaub Process.

When his convalescence was finally over, Huzenlaub had consented to an arrangement whereby Harwell was licensed to develop the new style of parboiled rice in the United States.

There was one condition: Harwell had to have a plant in operation within a year.

There was now a crying need for an infusion of hard cash. Harwell had a big stock of dried fruit on which he had already borrowed considerably. If he mortgaged his house and sold the fruit the proceeds could still never—even remotely—finance the purchase of the necessary building and equipment.

Harwell had a silent partner who now became plaintively vocal: "I'm 70 years old and not really vitally interested in investing in any project that isn't going to pay off for another ten years," he stated.

Forrest Mars had kept his ear tuned to these events: he had found Huzenlaub and had financed his trip to the United States, owned part of the Huzenlaub Process patent, and was well aware of the deal. Nevertheless he appreciated Harwell's persistence and enthusiasm.

"I have the ability to raise money," Mars informed the Houston food broker. "Sell me a half interest and I'll go into business with you." It was an offer the silent partner of Harwell found irresistibly attractive and he gladly left the new consortium to their own devices.

Forrest's Houston bank accountant questioned the wisdom of his loan application.

"What do you think I should pay for a half interest in this Harwell project?" Forrest asked. "I'm leaving for Chicago in 30 minutes. Send me the results of your thinking there."

The accountant did some digging, came up with a figure of $100,000, and was promptly told to make the offer. It was quickly accepted. Forrest was pleased with this transaction and offered the bank accountant a job which, some years later, developed into the presidency of the company.

* * * * *

Forrest was on yet another visit to Washington and had a long wait for his appointment with a government official. Boredom overcame him rapidly, and he soon struck up a conversation with a fellow supplicant. The man turned out to be an official with General Foods who had developed an instant coffee he thought would be deemed suitable for service rations. It afterwards became familiar as Instant Maxwell House.

* * * * *

Forrest was on yet another visit to Washington and had a long wait for his appointment with a government official. Boredom overcame him rapidly, and he soon struck up a conversation with a fellow supplicant. The man turned out to be an official with General Foods who had developed an instant coffee he thought would be deemed suitable for service rations. It afterwards became familiar as Instant Maxwell House.

* * * * *

The first major difficulty was in the rustling up of equipment. Steel and other metals were being requisitioned by the armed forces. Harwell doggedly combed through junk yards and disbanded mills and finally scrounged all he needed, including a new pressure tank and vacuum dryer from Dallas and a somewhat decrepit boiler from Galveston.

He arranged a lease on half a building which had been a rice warehouse. It was located at 2001 Nance Street in Houston. Towards the end of 1942 repairs were completed and the rather ramshackle enterprise had a home.

It was scarcely a palace.

The building was constructed of tin siding and had patched wooden floors. There was a boarded-off section about 30 feet square that uncomfortably housed eight associates. During winter they huddled around a pot-bellied stove in a small circumference of welcome warmth. However there was no barrier against Houston's summer humidity. It was akin to trying to survive in a load of wet hay.

A tower was constructed 100 feet high, on a reinforced foundation, to permit vertical feeding of the rice. The hot water tank at the top had to be checked hourly. The perilous ascent was by a succession of ship's ladders: one associate still gets out of breath recalling the journey.

In those days stairs were a luxury in factories. Elevators were a distant dream belonging to future halcyon times.

Much to everyone's pleased surprise the mill's antique machinery sputtered into uncertain life and did its work. The whole assembly strongly resembled the imaginative antics commonly associated with movie cartoons.

Gordon Harwell, unlike his new partner, Forrest Mars, relished publicity. When Nance Street was on the point of producing its very first batch of the new rice, he invited a number of dignitaries.

When all the guests had assembled, the steamer was started and the first sample confidently awaited in a few short minutes. A half-hour later frantic and noisy attempts were still being made to force the secondhand valves to work, but nothing availed.

The guests were then officially told what they had already guessed: there was a production hitch. Apparently the rice had expanded and couldn't make its way through the system. It took 24 hours to fix, and what was heralded as a grand opening turned out to be something less.

The hour had also arrived when the formerly immutable rice industry was due to receive a profound shock.

The Roosevelt administration had set the price at eight cents per pound — whatever the quality — so there was little incentive for the growers to furnish a superior grain.

The millers of ordinary rice could sell all they could bag to the government — merely coating it with the familiar, but eminently satisfactory, mixture of talc and glucose. The white appearance was still greatly prized and devoutly maintained.

In November 1942 the Houston Post headlined a front-page story: "Gulf Coast Rice Industry is Due to Make Amazing Strides." The ranch farm editor of the time went on to report that the Texas rice industry was going to be in the spotlight of the world after the war because of the new rice. He quoted Forrest as saying, "It's the one great improvement destined to do the most good in modern times."

The story was accompanied by a rare picture of Forrest studying some rice while being rather solemnly observed by Harwell. The picture suggested the two men were uncomfortable together. It was accurate: the business relationship of Harwell and Mars was conducted in an atmosphere of increasing friction.

There was no question that the rice market into which Forrest and Harwell had precipitated themselves was not ready to pay the extra costs (over ordinary white rice). The ordinary civilian did not have the option. The armed forces bought all the product.

Harwell made a beeline to Washington and demonstrated to the officials there, who were charged with the feeding of millions of men now in uniform, the superior attributes of the new type rice.

The government moguls took a surprisingly short time to agree; the advantages were immediately apparent. They realized the new process would be especially valuable when supplying field rations for troops in any part of the world.

"You could take a sack of it, float it off a beach at Okinawa if you wanted to, and it wouldn't hatch out and crawl away," one official later declared with enthusiasm. (Weevils often infested ordinary rice.)

The Huzenlaub Process protected the rice when delivered through air drops by the military to their troops in the field. Other cereals and rice not using this process often went to waste.

With a few flourishes of the legislative pen the government announced the armed forces would purchase the entire output of the new plant at Houston for the duration of the war. So important did they perceive this supplier to be that they subsequently provided financial assistance for a new facility.

As with sugar-shell candy, history repeated itself—a tendency which students have noticed. The immediate and important needs of the men and women at war were often best served by innovative products, specifically designed for easy, convenient use.

The New Orleans Rice Journal published a speech made by Gordon Harwell in Houston:

"Food fights for freedom! Today in war, tomorrow in peace! It is with considerable pride we have supplied the United States Army with our product, Converted rice, for more than a year and a half. During this time we have had the satisfaction of knowing it has moved into mess kitchens of army camps behind the fighting fronts in Africa, Australia, England, France and many other places.

"It has gone to the lines of battle where the fighting is heaviest. I wish to quote from a letter received from Mess Sergeant Hamrick. His father is one of our most valued associates working on Nance Street. Mess Sergeant Hamrick is now in action somewhere along the Siegfried Line. I quote:

"Dear Dad: I am always interested in hearing from you and about your work in your rice plant. And I'm very glad to tell you that it is following us right along as we move forward. The men are certainly crazy about your rice and it's a big help to me, since it's so easy to cook. Keep up the good work, Dad!"

On the home front there was fresh interest in the newfangled rice. It came from the prestigious Campbell Soup Company: white rice broke down during processing for their popular soups. So serious was the problem that Campbell had been importing rice from India through a special licence permitting it to enter the US without duty.

Campbell became early admirers of the Converted brand rice. They were one of the first major industrial buyers, and their orders have been on the books ever since.

The essential symbol of the timeclock was present on Nance Street. All associates were required to punch in. The constant stream of freight cars often blocked the street leading to the plant. On one such occasion associates watched askance as Forrest drove up in his distinctive red Ford convertible, perceived the situation, and, without hesitation, leapt through the open doors of a slowly moving boxcar and out the other side. He reached the office on time.

The Quartermaster-General, virtually the only customer, had a considerable influence on decisions affecting the plant's operation. This influential official realized that Nance Street was never going to be adequate for the armed forces' special needs.

As a first step he asked Forrest to move to Houston. (The Quartermaster had had satisfactory dealings with Forrest on sugar-shell candy. He was also fully cognizant of Forrest's successes in establishing the business in England and rejuvenating the Chicago factory.) He thought Harwell would profit from some underpinning.

Forrest accordingly moved his family—at that time resident in New Jersey — to Texas: first to an apartment which was part of the Lamar Hotel in Houston, subsequently to a rented house, then to a purchased one. John and Jacqueline moved with their parents; Forrest, Jr. was away at school. The Mars family quickly became involved in community life.

Forrest now personally encountered a barrage of requests from the bank about the repayment of loans. He also dealt with the shortages of essentials necessary to keep the plant churning out needed product.

Forrest urged his partner Harwell to badger the government to provide assistance; one thing the two partners shared was an uncommon zeal and undying faith in their Converted brand rice.

About a year after Nance Street started, the Defence Plant Corporation supplied funds to sponsor a new plant to aid the war effort. The site agreed for the project was on Clinton Drive in Houston.

Ground-breaking ceremonies for the new Converted brand rice plant were held in Houston on 30 September 1944. Among those taking part in the event were several representatives from the Department of Defense, consul members from five South American countries as well as from China and Mexico and, of course, Mars and Harwell.

The new mill came into operation just before the summer of 1945. It handled over 20 tons of rice per day at the beginning and twice that amount very shortly afterwards.

After the war the Quartermaster no longer needed a rice mill and it was put up for sale. Mars and Harwell were high bidders; the plant they had worked so hard to create and then expand became —with the help of a variety of loans —their property.

They had obtained more than bricks and mortar: the hectic requirements of wartime had taught them how to make the Huzenlaub Process work on a commercial scale.

Most importantly, the government was repaid in full for its investment—a claim that, unfortunately, could be made for very few war plants in the US.

The ill-matched partnership had the means and the knowledge to make their product; they now urgently required more domestic customers to buy it.

Huzenlaub, however, evinced little desire to confront these mundane problems. Forrest and Harwell were not compatible with his inventive nature. He folded his tent, sold his interests, and left the United States for whatever challenge Australia could provide.

Converted brand rice was still selling briskly to the armed forces even as they were being deactivated. As the uniformed users of the product dwindled fast, the surplus at Clinton Drive reached unmanageable levels.

Selling forays to head off a crisis uncovered willing customers in Cuba: this country's citizens soon absorbed nearly a third of the plant's capacity.

But the solution to Clinton Drive's sales shortfall had to be found inside the borders of the continental US. The problem was clear — almost exactly parallel to that of M&M's candies — Americans had to be convinced of the merits of Converted brand rice.

The first major difficulty was in the rustling up of equipment. Steel and other metals were being requisitioned by the armed forces. Harwell doggedly combed through junk yards and disbanded mills and finally scrounged all he needed, including a new pressure tank and vacuum dryer from Dallas and a somewhat decrepit boiler from Galveston.

He arranged a lease on half a building which had been a rice warehouse. It was located at 2001 Nance Street in Houston. Towards the end of 1942 repairs were completed and the rather ramshackle enterprise had a home.

It was scarcely a palace.

The building was constructed of tin siding and had patched wooden floors. There was a boarded-off section about 30 feet square that uncomfortably housed eight associates. During winter they huddled around a pot-bellied stove in a small circumference of welcome warmth. However there was no barrier against Houston's summer humidity. It was akin to trying to survive in a load of wet hay.

A tower was constructed 100 feet high, on a reinforced foundation, to permit vertical feeding of the rice. The hot water tank at the top had to be checked hourly. The perilous ascent was by a succession of ship's ladders: one associate still gets out of breath recalling the journey.

In those days stairs were a luxury in factories. Elevators were a distant dream belonging to future halcyon times.

Much to everyone's pleased surprise the mill's antique machinery sputtered into uncertain life and did its work. The whole assembly strongly resembled the imaginative antics commonly associated with movie cartoons.

* * *

Gordon Harwell, unlike his new partner, Forrest Mars, relished publicity. When Nance Street was on the point of producing its very first batch of the new rice, he invited a number of dignitaries.

When all the guests had assembled, the steamer was started and the first sample confidently awaited in a few short minutes. A half-hour later frantic and noisy attempts were still being made to force the secondhand valves to work, but nothing availed.

The guests were then officially told what they had already guessed: there was a production hitch. Apparently the rice had expanded and couldn't make its way through the system. It took 24 hours to fix, and what was heralded as a grand opening turned out to be something less.

The hour had also arrived when the formerly immutable rice industry was due to receive a profound shock.

* * *

Rice had to be bought at auction. But quality varied from farm to farm and there was a troublesome fixed price structure to endure.The Roosevelt administration had set the price at eight cents per pound — whatever the quality — so there was little incentive for the growers to furnish a superior grain.

The millers of ordinary rice could sell all they could bag to the government — merely coating it with the familiar, but eminently satisfactory, mixture of talc and glucose. The white appearance was still greatly prized and devoutly maintained.

In November 1942 the Houston Post headlined a front-page story: "Gulf Coast Rice Industry is Due to Make Amazing Strides." The ranch farm editor of the time went on to report that the Texas rice industry was going to be in the spotlight of the world after the war because of the new rice. He quoted Forrest as saying, "It's the one great improvement destined to do the most good in modern times."

The story was accompanied by a rare picture of Forrest studying some rice while being rather solemnly observed by Harwell. The picture suggested the two men were uncomfortable together. It was accurate: the business relationship of Harwell and Mars was conducted in an atmosphere of increasing friction.

There was no question that the rice market into which Forrest and Harwell had precipitated themselves was not ready to pay the extra costs (over ordinary white rice). The ordinary civilian did not have the option. The armed forces bought all the product.

Harwell made a beeline to Washington and demonstrated to the officials there, who were charged with the feeding of millions of men now in uniform, the superior attributes of the new type rice.

The government moguls took a surprisingly short time to agree; the advantages were immediately apparent. They realized the new process would be especially valuable when supplying field rations for troops in any part of the world.

"You could take a sack of it, float it off a beach at Okinawa if you wanted to, and it wouldn't hatch out and crawl away," one official later declared with enthusiasm. (Weevils often infested ordinary rice.)

* * * * *

"Weevils lay their eggs into exceedingly small holes which they drill with their mandibles into the surfaces of stored grains. In these holes the eggs develop into larvae and the moisture and food required by them are derived from the grain kernel. Weevils isolated with the Huzenlaub Process (converted rice), whether in small or large numbers, will die within a few days and will not multiply. The almost glasshard surface of rice and cereals under the Huzenlaub Process makes it impossible for weevil's mandibles to provide a hole for their eggs."

* * * * *

The Huzenlaub Process protected the rice when delivered through air drops by the military to their troops in the field. Other cereals and rice not using this process often went to waste.

With a few flourishes of the legislative pen the government announced the armed forces would purchase the entire output of the new plant at Houston for the duration of the war. So important did they perceive this supplier to be that they subsequently provided financial assistance for a new facility.

As with sugar-shell candy, history repeated itself—a tendency which students have noticed. The immediate and important needs of the men and women at war were often best served by innovative products, specifically designed for easy, convenient use.

* * *

The New Orleans Rice Journal published a speech made by Gordon Harwell in Houston:

"Food fights for freedom! Today in war, tomorrow in peace! It is with considerable pride we have supplied the United States Army with our product, Converted rice, for more than a year and a half. During this time we have had the satisfaction of knowing it has moved into mess kitchens of army camps behind the fighting fronts in Africa, Australia, England, France and many other places.

"It has gone to the lines of battle where the fighting is heaviest. I wish to quote from a letter received from Mess Sergeant Hamrick. His father is one of our most valued associates working on Nance Street. Mess Sergeant Hamrick is now in action somewhere along the Siegfried Line. I quote:

"Dear Dad: I am always interested in hearing from you and about your work in your rice plant. And I'm very glad to tell you that it is following us right along as we move forward. The men are certainly crazy about your rice and it's a big help to me, since it's so easy to cook. Keep up the good work, Dad!"

On the home front there was fresh interest in the newfangled rice. It came from the prestigious Campbell Soup Company: white rice broke down during processing for their popular soups. So serious was the problem that Campbell had been importing rice from India through a special licence permitting it to enter the US without duty.

Campbell became early admirers of the Converted brand rice. They were one of the first major industrial buyers, and their orders have been on the books ever since.

* * *

The Nance Street building was a beginning, but just barely.

Rice was loaded in tattered 162-pound bags—the equivalent of a "barrel"—and placed on railway cars (transport trucks were not known in those days). These were brought to the open-sided warehouse and rather unceremoniously unloaded.

Some of the railway cars, through general buffeting and lack of repair, had holes through which a constant trickle of grain emanated. This brought joy to flocks of hovering birds.

The rice was unloaded and promptly processed and milled, then returned to the cars which had transported it to Nance Street. Storage space was thought of, contemptuously, as a frill. There was none.

Working conditions were less than perfect, but the new company paid wages ten percent above the going rate; moreover, they offered a guarantee of 50 weeks' work in an industry notorious for providing seasonal employment at best.

The Nance Street building was a beginning, but just barely.

Rice was loaded in tattered 162-pound bags—the equivalent of a "barrel"—and placed on railway cars (transport trucks were not known in those days). These were brought to the open-sided warehouse and rather unceremoniously unloaded.

Some of the railway cars, through general buffeting and lack of repair, had holes through which a constant trickle of grain emanated. This brought joy to flocks of hovering birds.

The rice was unloaded and promptly processed and milled, then returned to the cars which had transported it to Nance Street. Storage space was thought of, contemptuously, as a frill. There was none.

Working conditions were less than perfect, but the new company paid wages ten percent above the going rate; moreover, they offered a guarantee of 50 weeks' work in an industry notorious for providing seasonal employment at best.

* * *

The essential symbol of the timeclock was present on Nance Street. All associates were required to punch in. The constant stream of freight cars often blocked the street leading to the plant. On one such occasion associates watched askance as Forrest drove up in his distinctive red Ford convertible, perceived the situation, and, without hesitation, leapt through the open doors of a slowly moving boxcar and out the other side. He reached the office on time.

* * *

The Quartermaster-General, virtually the only customer, had a considerable influence on decisions affecting the plant's operation. This influential official realized that Nance Street was never going to be adequate for the armed forces' special needs.

As a first step he asked Forrest to move to Houston. (The Quartermaster had had satisfactory dealings with Forrest on sugar-shell candy. He was also fully cognizant of Forrest's successes in establishing the business in England and rejuvenating the Chicago factory.) He thought Harwell would profit from some underpinning.

Forrest accordingly moved his family—at that time resident in New Jersey — to Texas: first to an apartment which was part of the Lamar Hotel in Houston, subsequently to a rented house, then to a purchased one. John and Jacqueline moved with their parents; Forrest, Jr. was away at school. The Mars family quickly became involved in community life.

Forrest now personally encountered a barrage of requests from the bank about the repayment of loans. He also dealt with the shortages of essentials necessary to keep the plant churning out needed product.

Forrest urged his partner Harwell to badger the government to provide assistance; one thing the two partners shared was an uncommon zeal and undying faith in their Converted brand rice.

About a year after Nance Street started, the Defence Plant Corporation supplied funds to sponsor a new plant to aid the war effort. The site agreed for the project was on Clinton Drive in Houston.

Ground-breaking ceremonies for the new Converted brand rice plant were held in Houston on 30 September 1944. Among those taking part in the event were several representatives from the Department of Defense, consul members from five South American countries as well as from China and Mexico and, of course, Mars and Harwell.

The new mill came into operation just before the summer of 1945. It handled over 20 tons of rice per day at the beginning and twice that amount very shortly afterwards.

After the war the Quartermaster no longer needed a rice mill and it was put up for sale. Mars and Harwell were high bidders; the plant they had worked so hard to create and then expand became —with the help of a variety of loans —their property.

They had obtained more than bricks and mortar: the hectic requirements of wartime had taught them how to make the Huzenlaub Process work on a commercial scale.

Most importantly, the government was repaid in full for its investment—a claim that, unfortunately, could be made for very few war plants in the US.

* * *

The ill-matched partnership had the means and the knowledge to make their product; they now urgently required more domestic customers to buy it.

Huzenlaub, however, evinced little desire to confront these mundane problems. Forrest and Harwell were not compatible with his inventive nature. He folded his tent, sold his interests, and left the United States for whatever challenge Australia could provide.

Converted brand rice was still selling briskly to the armed forces even as they were being deactivated. As the uniformed users of the product dwindled fast, the surplus at Clinton Drive reached unmanageable levels.

Selling forays to head off a crisis uncovered willing customers in Cuba: this country's citizens soon absorbed nearly a third of the plant's capacity.

* * *

But the solution to Clinton Drive's sales shortfall had to be found inside the borders of the continental US. The problem was clear — almost exactly parallel to that of M&M's candies — Americans had to be convinced of the merits of Converted brand rice.

* * * * *

"If we came across a damaged package, we bought it immediately. Everyone who worked with us had a personal sense of identity with our product. This wasn't a policy, it was just a generally accepted way we wanted to do business."

* * * * *

Rather than waste time dwelling on their possible fate, Harwell and Mars got in touch with a big-time Chicago advertising agency, Leo Burnett.

Burnett made an initial recommendation. In a blinding flash of the utterly obvious, they suggested that the partners "do something about sales—and fast." The agency people also put forward tangible ways to achieve this desirable objective. They knew of a crackerjack marketing director who had reportedly done wonders for a local dog food company. They suggested that he be weaned away and hired to get Converted brand rice distributed right across the country.

This course of action was adopted, and proved to be a very productive step indeed.

Hiring food brokers to do the selling in lieu of creating a direct salesforce was an early bone of contention. Harwell argued that rice was an infrequent purchase — nothing at all like candy. A company-owned salesforce would be a guaranteed money-loser. Forrest had succeeded with his own sales associates in confectionery; it was extremely hard to convince him that the vital function of purveying his rice should be entrusted to outsiders. Forrest approached the whole proposal with apprehension, although he was considerably attracted to the money-saving aspect of it.

Harwell and the newly appointed sales director set out on a long journey to convince the nation's most desirable food brokers they should take on the new line. This was no sinecure.

Many brokers had made a respectable profit "on the side" by their own haphazard repackaging of ordinary white rice which they distributed to their individual market areas. They were frank in their assessment of rice: it was a "belly-filling" type of product, ill-suited to "fancy" packaging. They had great trouble perceiving any added value in the new rice; ergo, why should it command such an elevated price?

The sanitary, factory-packed package, as opposed to bulky or leaky bags, was an early and generally effective selling tool for Converted brand rice. One of Harwell's first print advertisements depicts a cat sleeping on a bag of rice.

The associates from Converted brand rice promised advertising support. They offered special rewards for outstanding sales. If millions of servicemen and women had consumed the product during the war, then they appreciated the undisputed quality. The veterans were built-in customers just waiting for some alert broker to make it available. Now that peace had finally broken out, one of the fruits of victory was the vast improvement Converted brand rice offered. It was the right moment for sales-forces with vision. A golden rainbow awaited.

The arguments worked. The broker network was put in place right across the country. A major advance had occurred.

The next barrier came in logical sequence. The great American public had to be made aware of Converted brand rice. Most of all, that elusive element had to be found which would make them go to the stores and demand it.

Rice had been anathematized by the statement, "Rice is ... just rice." This stigma had to be removed, obliterated. But how?

Until Mars and Harwell emerged on the rice scene, no one had ever attempted to put a brand name on the product. It was always sold by weight, generally in a completely unadorned, uninteresting plain bag. "Buy me if you dare," it seemed to say to the consumer. To attempt anything more sophisticated was considered ludicrous, a mild form of insanity.

Harwell and Mars ignored the widely believed doctrines. After all, their product really was different: it was virtually impervious to the voracious weevil; it held up well on steam tables; it cooked better under all circumstances; and, above all, the grains stayed separate and fluffy after cooking. The partners knew their product was superior. They knew it, now others had to be provided with that knowledge.

Obviously advertising was needed. The Leo Burnett agency in Chicago designed a package employing the new slogan: "Each grain salutes you!" This was used for several years, but nagging at the back of Harwell's mind was the fact that the product still lacked a memorable personality.

A number of additional brand names were kicked around in frequent discussions, with "Marwell" briefly considered. It was a somewhat over-contrived and awkward coupling of the two partners' names. The agency, when informed of this particular creative emanation, were polite but adamant: "It means absolutely nothing."

Harwell had long marketed some products from New Orleans under the name Uncle Ben's. This range included jams and jellies, as well as blackstrap molasses. (Indeed Harwell had sold Uncle Ben's Plantation Rice in the early 1930s, a brand of plain white rice which he had packaged for his brokerage area.) He now spoke to his principals who quickly consented to give him the name Uncle Ben's for use on his new Converted brand rice.

It was a particularly happy choice because, coincidentally, there was a black rice-farmer named Ben in Beaumont, Texas, who had built an enviable reputation. It was said he grew the finest in the state. When speaking of quality rice, admiring farmers from all around compared their crops to Uncle Ben's: the name became a synonym for the best.

When the name was suggested to the advertising agency, they enthusiastically endorsed it.

Uncle Ben's seemed to fit naturally and comfortably. "Why didn't we think of it?" was the cry. These words are always a happy augury for brand-name success.

Finding a face to fit the name occurred easily.

Harwell and the executives from the Chicago agency frequently lunched in the prestigious Tavern Club which fills the top floor of the office building occupied by the Leo Burnett agency.

The club, habitually used by advertising people who form the bulk of its membership, is still extant these many years after in a city renowned for its love of good food.

The hatcheck attendant was a genial gentleman, Frank Brown, whose jovial disposition made him a great favourite of the habitues. Harwell thought him perfection as the image of Uncle Ben. Once more the agency wholeheartedly agreed and, on a later date, so did Forrest.

Brown consented to have his portrait painted and for his trouble received $500. The original still hangs in the offices on Clinton Drive in Houston.

Brown's image has since appeared in all civilized countries of the globe, in multitudes of impressions. His cordial expression and distinctive features are an indelible part of Uncle Ben's Converted brand rice. He provided a singular "personality" to what had previously been regarded as a generic, bland food.

Burnett made an initial recommendation. In a blinding flash of the utterly obvious, they suggested that the partners "do something about sales—and fast." The agency people also put forward tangible ways to achieve this desirable objective. They knew of a crackerjack marketing director who had reportedly done wonders for a local dog food company. They suggested that he be weaned away and hired to get Converted brand rice distributed right across the country.

This course of action was adopted, and proved to be a very productive step indeed.

Hiring food brokers to do the selling in lieu of creating a direct salesforce was an early bone of contention. Harwell argued that rice was an infrequent purchase — nothing at all like candy. A company-owned salesforce would be a guaranteed money-loser. Forrest had succeeded with his own sales associates in confectionery; it was extremely hard to convince him that the vital function of purveying his rice should be entrusted to outsiders. Forrest approached the whole proposal with apprehension, although he was considerably attracted to the money-saving aspect of it.

Harwell and the newly appointed sales director set out on a long journey to convince the nation's most desirable food brokers they should take on the new line. This was no sinecure.

Many brokers had made a respectable profit "on the side" by their own haphazard repackaging of ordinary white rice which they distributed to their individual market areas. They were frank in their assessment of rice: it was a "belly-filling" type of product, ill-suited to "fancy" packaging. They had great trouble perceiving any added value in the new rice; ergo, why should it command such an elevated price?

The sanitary, factory-packed package, as opposed to bulky or leaky bags, was an early and generally effective selling tool for Converted brand rice. One of Harwell's first print advertisements depicts a cat sleeping on a bag of rice.

The associates from Converted brand rice promised advertising support. They offered special rewards for outstanding sales. If millions of servicemen and women had consumed the product during the war, then they appreciated the undisputed quality. The veterans were built-in customers just waiting for some alert broker to make it available. Now that peace had finally broken out, one of the fruits of victory was the vast improvement Converted brand rice offered. It was the right moment for sales-forces with vision. A golden rainbow awaited.

The arguments worked. The broker network was put in place right across the country. A major advance had occurred.

The next barrier came in logical sequence. The great American public had to be made aware of Converted brand rice. Most of all, that elusive element had to be found which would make them go to the stores and demand it.

Rice had been anathematized by the statement, "Rice is ... just rice." This stigma had to be removed, obliterated. But how?

Until Mars and Harwell emerged on the rice scene, no one had ever attempted to put a brand name on the product. It was always sold by weight, generally in a completely unadorned, uninteresting plain bag. "Buy me if you dare," it seemed to say to the consumer. To attempt anything more sophisticated was considered ludicrous, a mild form of insanity.

Harwell and Mars ignored the widely believed doctrines. After all, their product really was different: it was virtually impervious to the voracious weevil; it held up well on steam tables; it cooked better under all circumstances; and, above all, the grains stayed separate and fluffy after cooking. The partners knew their product was superior. They knew it, now others had to be provided with that knowledge.

Obviously advertising was needed. The Leo Burnett agency in Chicago designed a package employing the new slogan: "Each grain salutes you!" This was used for several years, but nagging at the back of Harwell's mind was the fact that the product still lacked a memorable personality.

A number of additional brand names were kicked around in frequent discussions, with "Marwell" briefly considered. It was a somewhat over-contrived and awkward coupling of the two partners' names. The agency, when informed of this particular creative emanation, were polite but adamant: "It means absolutely nothing."

Harwell had long marketed some products from New Orleans under the name Uncle Ben's. This range included jams and jellies, as well as blackstrap molasses. (Indeed Harwell had sold Uncle Ben's Plantation Rice in the early 1930s, a brand of plain white rice which he had packaged for his brokerage area.) He now spoke to his principals who quickly consented to give him the name Uncle Ben's for use on his new Converted brand rice.

It was a particularly happy choice because, coincidentally, there was a black rice-farmer named Ben in Beaumont, Texas, who had built an enviable reputation. It was said he grew the finest in the state. When speaking of quality rice, admiring farmers from all around compared their crops to Uncle Ben's: the name became a synonym for the best.

When the name was suggested to the advertising agency, they enthusiastically endorsed it.

Uncle Ben's seemed to fit naturally and comfortably. "Why didn't we think of it?" was the cry. These words are always a happy augury for brand-name success.

* * *

Finding a face to fit the name occurred easily.

Harwell and the executives from the Chicago agency frequently lunched in the prestigious Tavern Club which fills the top floor of the office building occupied by the Leo Burnett agency.

The club, habitually used by advertising people who form the bulk of its membership, is still extant these many years after in a city renowned for its love of good food.

The hatcheck attendant was a genial gentleman, Frank Brown, whose jovial disposition made him a great favourite of the habitues. Harwell thought him perfection as the image of Uncle Ben. Once more the agency wholeheartedly agreed and, on a later date, so did Forrest.

Brown consented to have his portrait painted and for his trouble received $500. The original still hangs in the offices on Clinton Drive in Houston.

Brown's image has since appeared in all civilized countries of the globe, in multitudes of impressions. His cordial expression and distinctive features are an indelible part of Uncle Ben's Converted brand rice. He provided a singular "personality" to what had previously been regarded as a generic, bland food.

* * *

With the package designed, Harwell and Mars commissioned the advertising agency to provide a comprehensive backup advertising campaign. Full-page, full-colour ads were placed by Leo Burnett in the very popular Life magazine which, at the time, was at the peak of its considerable circulation and popularity.

* * * * *

"Forrest asked me how much money we had lost in bad debts in the last three years. I told him: 'Not a penny' — I was mighty proud to be able to make that statement. 'Well, then, you're pretty stupid,' was the astonishing reply. 'You've got to lose some money if you're taking the necessary risks to build the business.'"

* * * * *

Taking the bull by the horns, the area selected for the initial push was no less than glittering New York City.

In a flamboyant style that never became typical for the company, Harwell gave an introductory banquet at Manhattan's plush Carlton House. Members of the media were invited to an "all-rice" menu from soup to dessert. The event was probably successful in business terms.

However it cost a scandalous $10,000 and was looked upon by Houston-bound associates as something bordering on wild extravagance. However, the sales of Uncle Ben's Converted brand rice never looked back.

By 1952 retail sales of Converted brand rice showed the company product in undisputed first place. Business to hospitals, restaurants, hotels, and government establishments began to thrive. The new rice was found to be ideal for large institutions.

All the marketing thrusts required large sums of money.

Profits were meagre: in 1948-49 (after the New York event) they were less than $10,000 — a small amount for so much effort.

In 1951 the company found itself in precarious financial condition. A hasty re-arrangement of finances salvaged the situation, but there were times when it was tough just meeting the payroll.

Taking the bull by the horns, the area selected for the initial push was no less than glittering New York City.

In a flamboyant style that never became typical for the company, Harwell gave an introductory banquet at Manhattan's plush Carlton House. Members of the media were invited to an "all-rice" menu from soup to dessert. The event was probably successful in business terms.

However it cost a scandalous $10,000 and was looked upon by Houston-bound associates as something bordering on wild extravagance. However, the sales of Uncle Ben's Converted brand rice never looked back.

By 1952 retail sales of Converted brand rice showed the company product in undisputed first place. Business to hospitals, restaurants, hotels, and government establishments began to thrive. The new rice was found to be ideal for large institutions.

All the marketing thrusts required large sums of money.

Profits were meagre: in 1948-49 (after the New York event) they were less than $10,000 — a small amount for so much effort.

In 1951 the company found itself in precarious financial condition. A hasty re-arrangement of finances salvaged the situation, but there were times when it was tough just meeting the payroll.

* * *

From the dark days of the company's history, which were directly after the war and during the time it took to get the brand established on the domestic market, sales to Cuba remained exceptionally buoyant and were a lifesaver during those struggles.

Rice is the most consumed grain in Cuba; it outdistances corn meal and wheat flour combined. Rice is the daily staple. The national dish — "arroz con polio" — consists of rice cooked with chicken.

The importance of rice in the Cuban diet is highlighted by the staggering consumption figures during the six years, 1935 to 1940. These vary from 450 to 500 million pounds annually — about 110 pounds per capita. This compares to only four pounds per capita consumption in the United States.

Cuba took one third of Clinton Drive's output and sold it under the name Tio Ben. It was not an easy market to handle. The ruling government of Batista appointed 20 wholesalers who together controlled all the import licences; when Cuba's own domestic rice crop was favourable, these were correspondingly reduced.

From the dark days of the company's history, which were directly after the war and during the time it took to get the brand established on the domestic market, sales to Cuba remained exceptionally buoyant and were a lifesaver during those struggles.

Rice is the most consumed grain in Cuba; it outdistances corn meal and wheat flour combined. Rice is the daily staple. The national dish — "arroz con polio" — consists of rice cooked with chicken.

The importance of rice in the Cuban diet is highlighted by the staggering consumption figures during the six years, 1935 to 1940. These vary from 450 to 500 million pounds annually — about 110 pounds per capita. This compares to only four pounds per capita consumption in the United States.

Cuba took one third of Clinton Drive's output and sold it under the name Tio Ben. It was not an easy market to handle. The ruling government of Batista appointed 20 wholesalers who together controlled all the import licences; when Cuba's own domestic rice crop was favourable, these were correspondingly reduced.

* * * * *

"If I could brand every rice kernel the way we identify M&M's I would be very happy."

-Forrest Mars, Sr.

* * * * *

In order to identify Tio Ben, little printed discs of the name were inserted in the 100-pound jute bags, reminiscent of the early days at M&M's.

Cuba was anxious to attract offshore rice mills, and now pressured the Uncle Ben's company to build a facility. Three sites were identified, one was chosen. The contractor was standing by with excavators at the ready. The $6 million expenditure was on the brink of approval. It appeared that native-grown rice would now be processed by Uncle Ben's on the island.

Pens were poised. Celebrations were in the planning stage. One week elapsed. In December 1959 Castro seized power and all plans abruptly terminated.

One-third of Uncle Ben's total business was gone in the proverbial flash. There was no time to lose; the company had to compensate for the tonnage Cuba had represented.

There were a number of rather urgent meetings held by Forrest with sales management after the Castro accession.

Emerging from one of these, Forrest espied a lonely figure at a remote corner of the office. "Who is that?" he enquired, and was told he was the merchandising assistant. "We don't have assistants," Forrest snapped. "Get him a suitcase and a passport and send him overseas to get us some business!"

To paraphrase the popular song, it was the start of something big. The export manager (newly and hastily appointed) found that indeed he possessed a suitcase and a passport. Using both he made a quick exit from Houston and headed for Switzerland, Greece, and Saudi Arabia.

In the last-named country he was in the city of Jeddah which was controlled by an absolute monarch. It so happened that the ritual of a convicted thief having his hand cut off was being performed publicly in the city square. Everyone was expected to attend.

Believing he should not — in any way — abuse the customs of the country, the Uncle Ben's representative dutifully witnessed this stomach-turning event. Later, in Houston, he narrated the horror of the circumstance to Forrest.

Forrest jumped up and pounded his fist on a desk. "Just what was afraid of," he thundered, "instead of coming back with an order, you were behaving just like a tourist!"

No less than 106 countries were to become part of Uncle Ben's export activity as it began to literally girdle the globe. The initial efforts and their subsequent successful results were the forerunners of present-day sales to affiliated companies. These companies now handle distribution of Uncle Ben's products in their local markets.

The largest producing mill outside the US is located in Olen, Belgium. This unit purchases brown parboiled rice in bulk lots from Clinton Drive. Olen then packages and sells the rice to countries in the European Economic Community.

After all, reasoned Forrest, you have to give the customer a good reason to buy your product. His sons endorse this basic premise: it is a major reason for their continued successes.

At Uncle Ben's, ongoing study of the USP frequently culminates in change. "Each grain salutes you!" probably predated Forrest's accession. In his early days came "Twice the natural B vitamins of ordinary rice," and, concurrent with the use of these words, the wrath and indignation of the whole rice-milling community.

In 1957 "Guaranteed fluffy" emerged, to be followed by "Rice without the surface starch that makes rice stick." These were succeeded in the US by "If you want the very best say 'uncle,' Uncle Ben's," and, most recently, "It really does make a difference!"

In April 1959 the corporate name became Uncle Ben's and serious thought was given to expanding the franchise.

Extension to quick-cooking rice was scarcely a quantum leap, and the idea was not exactly new; a major competitor had a product which had gained considerable public favour.

However, a goal was set: create a product with the fine finished appearance of Uncle Ben's Converted brand rice, with fewer "brokens" than the competitor, retaining the attributes of fast preparation.

Work had actually started on this project as far back as 1946. The trick was to freeze long-grain rice slowly, then let it dry slowly as well — time-consuming perhaps, but with the desirable result of very few fractured grains.

It took at least five years to translate the method from a home-freezer ice tray, to bench scale-tests in the laboratory, to finally winning a patent.

Consumer tests with small batches were conclusive: the product possessed considerable advantages over its competition. Such was the euphoria that a new factory — to produce quick-cooking rice and future line-extensions — was started on West-heimer Road in Houston, on the opposite end of the spreading city from Clinton Drive.

In 1961 the first phase of construction — a lofty water tank — rose on the newly purchased site out in the vast, untenanted suburban countryside. It was completed just in time to receive the full force of vicious Hurricane Carla. The wind and the rain came in the extravagant measure associated with a great natural disaster but the water tank stood fast and firm.

An indication of good things to come? The quick-cooking plant was pushed ahead and completed in 1962 without further unusual events.

The Uncle Ben's Quick Rice product was introduced with much fanfare in the hope it would follow in the Converted brand's footsteps.

Considerable energy and enthusiasm was expended to ensure its success, but nothing could avail against an unacceptably high retail price. While the quality was a considerable improvement over the competition, the consumer (the ultimate judge) rejected it. It was withdrawn in 1982.

Company associates felt they'd lost a dear friend, and the decision to withdraw the Quick Rice brand was a distressing blow to some industrial users. Finally a product had been developed that wouldn't break down in canning and freezing. The price was higher but, for their special uses, well worth it.

Attempts to devise new ways of making consumer versions of quick-cooking rice with quality results continue.

Today, Uncle Ben's Converted brand rice has the largest market among branded rices in the world.

It has not been all straight sailing as Milton has it: "Like a stately ship, courted by all the winds." There were some misadventures.

In the mid-60s an episode occurred which many associates would prefer to consign to outer darkness. This event illustrated, with painful clarity, that uniqueness by itself doesn't invariably ensure sales success.

Beans were and are a frequently consumed, inexpensive, and delicious food staple in American diets. In fact, the consumption of beans in the colder northern states far exceeds rice.

Uncle Ben's decided to participate in this action and market four varieties of beans that didn't need to soak overnight before cooking. They were navy, kidney, white, and pinto types.

Besides the cooking-time advantage, Uncle Ben's beans were also purportedly desirable because they prevented excessive flatulence— although this claim was never scientifically verified.

Sufficient advantage to justify the price differential eluded product. Lower storage and distribution costs were also attractive.

The economics looked good but the start-up costs then were beyond the resources of the company. The idea, unlike the product, was shelved.

Alexander Pope was right. "Hope springs eternal in the human breast." In the late 1970s Uncle Ben's purchased a small company which produced a french-fried-like food made with rice. Located near Chicago, its output was a delectable alternative to potato fries. Not enough consumers agreed, and it was withdrawn. It was called Suncrisp.

This catalogue of calamity may well be perceived as an indictment of an otherwise thriving and progressive organization. These attempts were spread over two decades, during which many solid advances were made by the associates of Uncle Ben's.

Stepping back to 1960, specialty rices were virtually unknown. The dog-eared stigma ("rice is rice") was to be finally set aside by the introduction of such exotics as Spanish and Curried flavours, to be followed over the years by a host of intrigu-ingly-named products aimed at making ordinary meals into gourmet treats.

Not the least of these innovations was the mixture of Uncle Ben's Converted brand rice and wild rice.

No more than 20 percent of the wild rice crop is successfully harvested; the Indians originally and exclusively performed this inefficient task by pulling the heads of the ripe rice over the side of the canoe, then tapping them with two sticks so that the kernels fell within their craft. About two weeks later they returned to determine if the stem carried any unharvested crop.

This system of harvesting is carried out in a small region of icy lakes in northern Minnesota and in neighbouring Canadian provinces. No other area in the world is known to produce the unique product naturally. It most resembles barley and is, botan-ically speaking, a form of grass.

Wild rice, despite its name, is a fragile crop, subject to damage by brisk winds, flash flooding, and unexpected freezes. These vicissitudes are frequent in the unforgiving clime.

Uncle Ben's was first to utilize wild rice in a prepared food. In fact, it was the first time that a product derived from the wild was incorporated into a widely distributed grocery food. The US Fish & Game Commission and the Canadian Department of Indian Affairs also had to give permission.

By 1964 the product had obviously become a winner: 75 percent of the total available wild rice supply was then directed to Uncle Ben's. But nature did not co-operate as demand strengthened. There was a chronic shortage of wild rice — the weather constantly threatened prospects for consistent supply.

Seeding lakes to expand the crop had been attempted but this ploy could not be termed hugely successful. Why not try growing wild rice in paddies?

By 1966 three 20-acre farms in Minnesota were being tested. By 1968, 300 acres were growing wild rice. Ten years later, the total was closer to 20,000 acres.

Even with combine harvesting, the yield has not improved markedly. The stubborn wild rice still prefers cold and windy Minnesota and Wisconsin, and does equally well in the unappealing frigidity of the isolated areas in Canada's prairie provinces: Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

Stalwart attempts have been made to grow it in California, mostly at the instigation of Uncle Ben's. Results point to a successful venture. There have also been hydroponic experiments and test acreage in Mississippi.

The competition began to sniff at the scent of success which the Uncle Ben's venture was wafting. However, competitive entries, at best, have had nominal impact.

Uncle Ben's created a new and revolutionary idea with a nearly unknown product which had been regarded as being in the particular and sometimes peculiar domain of the gourmet cook.

They had demonstrated conclusively that marketing adventures in rice were only as limited as human imagination.

Uncle Ben's have expanded their wild rice line vigorously; today a number of their products utilize this difficult, skittish grain that idiosyncratically regards the cold, windy waters of inclement wilderness areas as its most compatible habitat.

Ideas for using rice are not the exclusive domain of the food-service business. North American householders receive a barrage of suggestions every month.

For 18 months a highly skilled group of Chicago consultants have helped devise at least 2000 different recipes. These are distributed in a relentless stream to 800 newspapers.

The most-read pages in newspapers are the food pages. Informed editors look for recipes that keep ahead of current trends. Right now, "nouvelle cuisine" has been replaced by lighter, fresher foods — rice has been found to be so versatile that it is always at the cutting edge of new food vogues.

Uncle Ben's consultants and associates attend all important food editors' conferences; they have also appeared at meetings with food authorities who influence buying decisions.

Sometimes these meetings are fraught with peril and an ambassador's diplomacy is required.

On one occasion, the merits of Uncle Ben's products had just been extolled, with particular emphasis on the nature and character of Converted brand rice. One food writer, an enthusiastic exponent of the virtues of the Cuisinart, leapt to her feet with "wonderful ideas." She assured everyone that her beloved machine would puree the rice and make it sticky! This statement, the antithesis of Uncle Ben's efforts, caused black spots to appear before the eyes of company associates.

* * *

Houston's Westheimer Road building, completed in 1962, was expanded in 1966. At the same time, construction started on a new modern corporate office complex and research centre. This was also completed in 1966. A dry mix plant was added in 1975: the 40,000 square-foot facility included a modern automatic-packaging and materials-handling system, as well as the latest quality control testing equipment.

"There is a language distinct from English or American, that sounds a little like both. It is Texan. In this state a pleasant, sunny day is likely to be termed 'a mighty pretty day.' If an associate is away from his desk or in another part of the world, they will tell you he is "out of pocket." And they are loath to brand anyone a liar, even if they have indisputable proof. They will more probably say, 'he was careless with the truth."

-Forrest Mars, Sr.

* * * * *

In order to identify Tio Ben, little printed discs of the name were inserted in the 100-pound jute bags, reminiscent of the early days at M&M's.

Cuba was anxious to attract offshore rice mills, and now pressured the Uncle Ben's company to build a facility. Three sites were identified, one was chosen. The contractor was standing by with excavators at the ready. The $6 million expenditure was on the brink of approval. It appeared that native-grown rice would now be processed by Uncle Ben's on the island.

Pens were poised. Celebrations were in the planning stage. One week elapsed. In December 1959 Castro seized power and all plans abruptly terminated.

One-third of Uncle Ben's total business was gone in the proverbial flash. There was no time to lose; the company had to compensate for the tonnage Cuba had represented.

* * *

There were a number of rather urgent meetings held by Forrest with sales management after the Castro accession.

Emerging from one of these, Forrest espied a lonely figure at a remote corner of the office. "Who is that?" he enquired, and was told he was the merchandising assistant. "We don't have assistants," Forrest snapped. "Get him a suitcase and a passport and send him overseas to get us some business!"

* * *

To paraphrase the popular song, it was the start of something big. The export manager (newly and hastily appointed) found that indeed he possessed a suitcase and a passport. Using both he made a quick exit from Houston and headed for Switzerland, Greece, and Saudi Arabia.

In the last-named country he was in the city of Jeddah which was controlled by an absolute monarch. It so happened that the ritual of a convicted thief having his hand cut off was being performed publicly in the city square. Everyone was expected to attend.

Believing he should not — in any way — abuse the customs of the country, the Uncle Ben's representative dutifully witnessed this stomach-turning event. Later, in Houston, he narrated the horror of the circumstance to Forrest.

Forrest jumped up and pounded his fist on a desk. "Just what was afraid of," he thundered, "instead of coming back with an order, you were behaving just like a tourist!"

No less than 106 countries were to become part of Uncle Ben's export activity as it began to literally girdle the globe. The initial efforts and their subsequent successful results were the forerunners of present-day sales to affiliated companies. These companies now handle distribution of Uncle Ben's products in their local markets.

The largest producing mill outside the US is located in Olen, Belgium. This unit purchases brown parboiled rice in bulk lots from Clinton Drive. Olen then packages and sells the rice to countries in the European Economic Community.

* * *

Many operational elements set Mars units apart from other corporations. Integral to the group's management of its companies was the early adoption of the unique selling proposition — the familiar USP. This became the advertising slogan and, simultaneously, the pithy description of the product itself.Uncle Ben's was the first American plant to sell US long-grain rice to Saudi Arabia, who now purchase more of it from the US (in dollars) than any other foreign market does.

The first rice to that country was parboiled as dark as possible through special processing. Uncle Ben's believed the Saudi people preferred the murky colour as it denoted the grain had more and better health-giving properties.

A Saudi prince visited the Uncle Ben's Converted brand rice plant at Clinton Drive; special efforts were made to show him the processing of the dark grain. During his inspection the prince peered through a partly-open door and saw some regular Converted brand rice. "Why can't we have that?" he asked. "I like the colour." No one could think of any reasons; thereafter, regular rice was shipped to his country.

On a different occasion another Saudi prince confided to an Uncle Ben's associate that he had a familiar problem. "When I go home tomorrow," he said, "I must bring some souvenirs of my visit to my wives." He went on to say that he had to be careful not to make them jealous, as this would destroy the harmony he currently enjoyed. Finally he decided to buy each wife a bolt of cloth. "How many will you need?" the prince was asked. "Sixteen or seventeen," the royal husband said, "I forget exactly which."

The first rice to that country was parboiled as dark as possible through special processing. Uncle Ben's believed the Saudi people preferred the murky colour as it denoted the grain had more and better health-giving properties.

A Saudi prince visited the Uncle Ben's Converted brand rice plant at Clinton Drive; special efforts were made to show him the processing of the dark grain. During his inspection the prince peered through a partly-open door and saw some regular Converted brand rice. "Why can't we have that?" he asked. "I like the colour." No one could think of any reasons; thereafter, regular rice was shipped to his country.

On a different occasion another Saudi prince confided to an Uncle Ben's associate that he had a familiar problem. "When I go home tomorrow," he said, "I must bring some souvenirs of my visit to my wives." He went on to say that he had to be careful not to make them jealous, as this would destroy the harmony he currently enjoyed. Finally he decided to buy each wife a bolt of cloth. "How many will you need?" the prince was asked. "Sixteen or seventeen," the royal husband said, "I forget exactly which."

* * *

Before all the domestic and export efforts had begun to bear fruit, there was some substantial risk-taking. Quite naturally, Forrest required his partner to contribute equally to counter some heavy reverses and get the business on its feet. These infusions of capital became a regular and unpleasant aspect of the business for Harwell, who did not enjoy unlimited financial resources.

During one of the shutdowns which dotted the early history of Uncle Ben's, Harwell appeared in an ominously silent plant which was free of the clatter and hum of busy machines. "Let's make some noise around this place," he loudly suggested to the associates, "I find this too depressing."

By 1955 Forrest was doing the only thing he really knew how to do: he was planning expansion on a massive scale. Harwell thought these schemes were pie-in-the-sky, and almost financially daunting.

"Tell you what," said a somewhat bumptious Forrest, "you've got to have guts to make a business really big. You buy me out or I'll buy you out. Whichever way you want."

Harwell didn't take long to make up his mind. He accepted the offer to sell his stock to Forrest and departed from Uncle Ben's in December 1955.

Before all the domestic and export efforts had begun to bear fruit, there was some substantial risk-taking. Quite naturally, Forrest required his partner to contribute equally to counter some heavy reverses and get the business on its feet. These infusions of capital became a regular and unpleasant aspect of the business for Harwell, who did not enjoy unlimited financial resources.